Congratulations – you have just been elected to the Board of Directors of a nonprofit organization. You accept the position! You want to do the job right.

What do you need to do?

- First, familiarize yourself with the organization. Read, at a minimum: the Articles of Incorporation, the Bylaws, the Form 1023 (application for exemption from income tax), the mission statement, literature about the organization, the last two years of Form 990 tax returns, financial statements for the last two years, and the website. Ask questions if there is anything you don’t understand.

- Second, make sure you understand the basic legal/organizational structure. Is it a corporation? Is it a California nonprofit public benefit corporation? Is it tax- exempt? Is it a public charity or a private foundation? Is it controlled by, or affiliated with, another entity? How is the Board elected or appointed?

- Third, make sure you have a basic understanding of the duties of a director, including the duty of care and the duty of loyalty. Understand the process. See Section I of this outline.

- Fourth, make sure you have a basic understanding of the substantive legal requirements that govern the entity, enough so that you can spot problems and know when to ask legal counsel or other experts. See Sections II (charitable trust), III (tax law), and IV (Nonprofit Integrity Act) of this outline.

- Fifth, understand the ways in which a director can be protected from liability. See Section V.

CONTENTS

I. Basic Duties of Directors

II. Charitable Trust Obligations

III. Section 501(c)(3) – A Primer

IV. The Nonprofit Integrity Act (“NIA”)

V. Director Liability & Protections

This outline also contains the following appendix:

A. Bibliography of Resources

I. Basic Duties of Directors

A director needs to understand the legal structure of the entity he or she is serving.

California law recognizes three different types of nonprofit corporations: public benefit, mutual benefit, and religious. In addition, some charitable organizations are structured as trusts, rather than as corporations, and some nonprofit corporations doing work in California are actually incorporated in other states, such as Delaware. The legal structure of the organization, as well as the state of organization, does affect the issues addressed in this outline, although many of the general principles are the same. This outline assumes that we are working with a California nonprofit public benefit corporation. The law that governs California nonprofit public benefit corporations is the California Nonprofit Public Benefit Corporation Law (the “Law”), which appears in Sections 5110 et seq. of the California Corporations Code.

Normally, nonprofit public benefit corporations seek tax exemption under Section 501(c)(3) or 501(c)(4) of the Internal Revenue Code (the “Code”). This outline assumes that we are working with a Section 501(c)(3) public charity.

What are the duties of Directors of a California nonprofit public benefit corporation?

A. Corporate Governance: The Board of Directors. The best way for a director of a nonprofit corporation to avoid liability is to do his or her job correctly. First and foremost, each director must understand that the directors are responsible for the governance of the corporation. The Law requires that nonprofit public benefit corporations be governed by a Board of Directors, sometimes also referred to as a Board of Trustees (the “Board”). Section 5210 of the Law permits the Board to delegate authority but makes clear that the Board is ultimately responsible, under the law, for the charity’s acts and omissions.

A leading case on limits of delegation, popularly known as the Sibley case for the charitable hospital involved, was decided in the District of Columbia.2 There, the Board of Directors delegated the investment function to its Treasurer without any Board oversight. The court held that each of the directors breached his fiduciary duty to supervise the management of Sibley’s investments. The court reasoned:

A total abdication of the supervisory role . . . is improper . . . . A director who fails to acquire the information necessary to supervise investment policy or consistently fails even to attend the meetings at which such policies are considered has violated his fiduciary duty to the corporation. While a director is, of course, permitted to rely upon the expertise of those to whom he has delegated investment responsibility, such reliance is a tool for interpreting the expertise of those to whom he has delegated investment responsibility, such reliance is a tool for interpreting the delegate’s reports, not an excuse for dispensing with or ignoring such reports. A director whose failure to supervise permits negligent mismanagement by others to go unchecked has committed an independent wrong against the corporation.

A California court took a similar position when it invalidated a Board’s decision to delegate complete management and control of corporate property to a manager, merely requiring the manager to file periodic reports. The court stated:

California has recognized the rule that the board cannot delegate its function to govern. As long as the corporation exists, its affairs must be managed by the duly elected board. The board may grant authority to act, but it cannot delegate its function to govern. If it does so, the [management] contract is void.3

B. Standard of Care. In governing, directors have two basic duties: a duty of care to the corporation and a duty of loyalty. Both of these duties are expressed, together, in Section 5231 of the Law. Section 5231 provides that directors of charities are required by law to carry out their responsibilities as directors “in good faith, in a manner such director believes to be in the best interests of the corporation and with such care, including reasonable inquiry, as an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances.”4

As a practical matter, a director cannot carry out his or her duty of care without minimally doing the following:

- First and foremost, a director must attend meetings and read materials provided at meetings and in advance of meetings. A director cannot exercise a duty of care if the director is absent.

- Directors must be familiar with the organization they represent, including the mission as set forth in the Articles of Incorporation and in mission statements, the activities of the organization, and the organizational structure and key staff positions.

- Directors should have a basic working knowledge of the main tax laws that affect charities (e.g., Section 501(c)(3)). They should also have a working knowledge of the state charitable trust rules that govern the charitable assets of a corporation. (A substantive discussion of these two areas of law is beyond the scope of this outline. Section II, however, summarizes the charitable trust rules in California, since such a summary is not easily available.)

Fortunately, the Law permits directors to rely on experts. In performing their duties, directors are specifically allowed by Section 5231(b) of the Law to rely on information and opinions prepared or presented by corporate officers or employees; counsel, outside accountants, and other outside professionals; and Board committees on which the director does not serve, so long as –

(a) The director reasonably believes that the provider of the information or advice is competent and reliable as to the matter at hand, and

(b) The director “acts in good faith, after reasonable inquiry when the need therefor is indicated by the circumstances and without knowledge that would cause such reliance to be unwarranted.”The Law sets forth a separate, but similar standard for directors in making investments on behalf of a nonprofit corporation. Charities in California are governed by the “prudent person” investment rule, under Section 5240 of the Law. However, an otherwise imprudent investment is allowed if it is either authorized or required by “an instrument or agreement pursuant to which the assets were contributed to the corporation.”Directors will also want to have a general familiarity with the rules set forth in the Uniform Management of Institutional Funds Act (Probate Code Sections 18500 et. seq.).

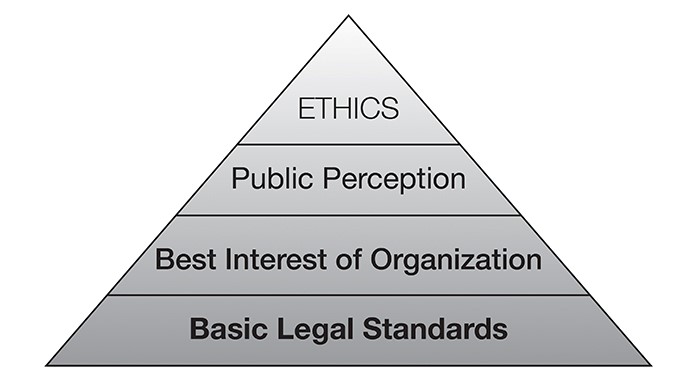

C. Conflicts of Interest. Section 5231 of the Law codifies two basic duties that have evolved through the case law – the duty of care and the duty of loyalty. The duty of care is fundamentally about acting prudently. The duty of loyalty is fundamentally about putting the interests of the corporation before the director’s own interests. In addition to the legal standards, charities often survive or perish based on their reputation and goodwill in the community. Perceived or actual conflicts of interest, as reported in the press, whether accurate or not, can often do great damage to the reputation of a charity. Damage to reputation can affect the ability of a charity to fundraise and obtain grants, which can obviously impact the fiscal health of the charity.

California law specifically addresses conflicts of interest in two statutes: Section 5227 and Section 5233.In addition, many charities seek to avoid conflicts of interest by adopting policies that prohibit certain types of conflicts and that require Board members to disclose potential conflicts, at least annually.A well-drafted conflicts of interest policy and disclosure form can provide a significant benefit to a charity.

1. The 49% Rule. Under Section 5227, not more than 49% of a public benefit corporation’s governing body may be composed of “interested directors,” defined as –

(a) Any person who has been compensated by the corporation for services within the last 12 months, and

(b) Any member of such a person’s family.

2. The Self-Dealing Rule. A self-dealing transaction, under California law,5 is a transaction to which the charity is a party and in which one or more directors has a material fi-nancial interest. Under Section 5233, a self-dealing transaction is proper only if all of the following conditions are met:6

(a) The charity entered into the transaction for its own benefit, and

(b) The transaction was fair and reasonable as to the charity at the time it entered into the transaction, and

(c) Before implementing the transaction or any part of it, all material facts regarding the transaction and the director’s interest in it were disclosed to the Board, and a majority of the disinterested directors then in office (without counting the vote of the financially interested director) –

(i) Determined, after reasonable inquiry under the circumstances, that the charity could not have obtained a better arrangement with reasonable effort, and

(ii) Formally approved the transaction.

Section 4958 of the Internal Revenue Code sets forth comparable, although slightly different rules for “excess benefit transactions.”It is very important to consider both state law and federal tax law when evaluating the substance and the procedures involved in a potential self-dealing transaction.

3. Conflicts of Interest Policies. In the authors’ view, a well-drafted conflict of interests policy will contain at least a basic statement of policy and an annual disclosure form. The depth and complexity of these forms will vary depending on the corporation, its activities, and its pre-existing relationship or affiliation with other for-profit or nonprofit entities. For example, a charity that was started by and is affiliated with a for-profit company will naturally have a different conflicts policy than a stand-alone charity with no prior affiliation. One example of a basic conflicts of interest policy is the following:

Charity encourages the active involvement of its staff and its directors in the community. In order to deal openly and fairly with actual and potential conflicts of interest that may arise as a consequence of this involvement, the Charity has adopted the following conflicts of interest policy.

1. A potential conflict of interest arises whenever the Charity contemplates a decision involving a vendor, consultant, or grantee with which a director or staff member is affiliated. Affiliation means the close involvement with a vendor, consultant, or grantee on the part of (a) a director of the Charity, (b) a staff member of the Charity, or (c) the spouse or equivalent, parents, or children of a director or staff member, within twelve months preceding the decision. Affiliation includes, but is not limited to, serving as a board member, employee, or consultant to the grantee, consultant, or vendor or doing business with the grantee, consultant or vendor.

2. A staff member who is affiliated with a prospective vendor,consultant, or grantee shall abstain from participating in any decision involving that vendor, consultant, or grantee. A director who is affiliated with a prospective vendor, consultant, or grantee shall abstain from voting with regard to any transaction between the Charity and that person and, after disclosing his or her interest, shall leave the room during discussion and while the vote is taken.

3. The Charity may engage in a transaction to award funds or to con-tract with a grantee, consultant, or vendor with whom a director or staff member is affiliated, only if the following conditions are met prior to the transaction:

A. The affiliated person shall disclose to the Board of Directors all material facts concerning the affiliation.

B. The Board of Directors shall review the material facts.The transaction may be approved only if a majority of the directors, not counting the vote of any director who is an affiliated person with regard to this transaction, concludes that:

(1) The proposed transaction is fair and reasonable to the Charity;

(2) The Charity proposes to engage in this transaction for its own purposes and benefits, and not for the benefit of the affiliated person; and

(3) The proposed transaction is the most beneficial arrangement which the Charity could obtain in the circumstances with reasonable effort.

4. The minutes of any meeting at which such a decision is taken shall record the nature of the affiliation and the material facts disclosed by the affiliated person and reviewed by the Board of Directors or its Executive Committee.

Overall, except for potential self-dealing actions, a director who acts in accordance with the Section 5231 duty of care “shall have no liability based upon any alleged failure to discharge the person’s obligations as a director, including . . . any actions or omissions which exceed or defeat a public or charitable purpose to which a corporation, or assets held by it, are dedicated.”7 Similarly, a director involved in a potential self-dealing situation will not be liable if the Board follows the procedures set forth in Section 5233, described above.

II. Charitable Trust Obligations

In exercising a director’s duty of care, he or she needs to have a working knowledge of at least two basic bodies of law. The first is the charitable trust doctrine, addressed in this Section II, and the second is Section 501(c)(3) of the Code, addressed in the next Section.

Common law, dating back to Elizabethan England, has evolved a “charitable trust” doctrine. Even though most nonprofit law is statutory and the enforcement powers of the California Attorney General are set forth in the Law, the substantive charitable trust rules that the AG enforces are largely creatures of case law.

In Pacific Home v. County of Los Angeles, 41 Cal. 2d 844, 852 (1953), the California Supreme Court announced the charitable trust doctrine:

All the assets of a corporation organized solely for charitable purposes must be deemed to be impressed with a charitable trust by virtue of the express declaration of the corporation’s purposes, and notwithstanding the absence of any express declaration by those who contribute such assets as to the purpose for which the contributions are made. In other words, the acceptance of such assets under these circumstances establishes a charitable trust for the declared corporate purposes as effectively as though the assets had been accepted from a donor who had expressly provided in the instrument evidencing the gift that it was to be held in trust solely for such charitable purposes.

As initially formulated in Pacific Home, the charitable trust doctrine looked to language in Articles of Incorporation and other formal manifestations of declared corporate purposes. The court reasoned that donor intent and donor restrictions need not be express but could be inferred from donee representations that are written and formal.

Eleven years later, the California Supreme Court took the next step in expanding the charitable trust doctrine when it dropped the requirement that donee representations be written and formal and accepted them as equivalent to express donor restrictions even where they were oral and informal. Thus, a college of osteopathic medicine could not change to become a college of allopathic medicine when it had “held out to the public” that it was a college of osteopathic medicine and “solicited and received donations for use in teaching . . .osteopathy.”Holt v. College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons, 61 Cal. 2d 750 (1964).

Then, in Queen of Angels Hospital v. Younger, 66 Cal. App. 359, 368 (1977), the court broadened the application of the charitable trust doctrine to encompass a wide array of donee acts and representations. The court considered the language of the Articles of Incorporation, which included the name “Queen of Angels Hospital” and a hospital purpose clause. The court also noted that Queen had operated a hospital since 1927 and stated (p.368):

Queen also represented to the public that it was a hospital. In its statement to the Franchise Tax Board, it stated that it was in the “business of running a hospital.” Similar statements were made to the Internal Revenue Service and Los Angeles county tax authorities. Funds were solicited from the public for the hospital or hospital purposes. Such acts further bind Queen to its primary purpose of operating a hospital.

The result, in Queen of Angels, was that a charitable organization that operated a hospital and raised funds based on its representations as a hospital, was prevented from abandoning the operation of a hospital and operating a medical clinic instead. See also In Re Metropolitan Baptist Church of Richmond, Inc., 48 Cal. App. 3d 850 (1975) (representing itself as a fundamentalist Baptist church located in Richmond, California, the church was prohibited from distributing its assets on dissolution to distant Baptist churches and required to distribute them to fundamentalist Baptist churches nearest geographically to Richmond).

The Queen of Angels decision also has continuing importance for its treatment of bonuses and settlements. Queen expected to receive a significant positive cash flow from the proposed lease of its hospital, which was to run for 25 years with two options for 10-year extensions. The lease amount was $800,000 during the first two years and $1 million annually thereafter. The Franciscan Sisters submitted a claim for $16 million for the value of the Sisters’ past services. The Board of Directors of Queen unanimously accepted the validity of the claim and entered into a settlement agreement whereby Queen would provide for the retirement of each sister by paying her approximately $200 per month for life, for an initial annual cost of approximately $300,000. The trial court upheld the Attorney General’s objections to the proposed payments: there was no evidence to support the Sisters’ claim; Queen had no legal obligation to pay the Sisters; the settlement agreement was invalid and would constitute an improper diversion of charitable assets if implemented. The court of appeals affirmed, with the result that Attorney General often relies on Queen of Angels in support of these two propositions:

- Despite sympathetic circumstances, payment by a charity of bonuses, including unearned retirement amounts, may constitute an improper diversion of charitable assets unless they are made pursuant to a binding legal obligation to pay.

- Although a charity is generally empowered to settle disputes without the consent of the Attorney General, a settlement agreement that “was not a proper exercise of sound business judgment” may be invalid and unenforceable.8

The charitable trust doctrine varies from state to state. In some states, the doctrine means little more than assets of a charitable organization must be used for charitable purposes. In California, however, the courts have adopted a strict construction of the charitable trust doctrine, which contains these rules:

- A donor’s charitable contributions to a nonprofit corporation are subject to any valid legal restriction imposed by the donor at the time of contribution. These restrictions impose a charitable trust on the assets, binding on the charitable recipient.9

- Even where a donor imposes no express restriction, assets accepted by a nonprofit corporation are restricted by operation of law and may only be used for the specific charitable purposes set forth in the corporation’s Articles of Incorporation.10

- These restrictions apply not only to contributions and donations received and accepted by a nonprofit corporation but also to revenues generated by it from the performance of its charitable activities. Revenues, like contributions, are impressed with a charitable trust and may only be used for the charitable purposes set forth in the Articles of Incorporation at the time the revenues are received.11

- Unless made pursuant to a binding obligation to pay, the payment of bonuses by a charity to its employees constitutes an improper diversion of charitable assets.12

- Charitable trust restrictions, once imposed, continue to apply to assets impressed with a charitable trust even if a corporation later changes its purposes, dissolves and distributes its assets, or transfers its assets to another charity without receiving full consideration. Charitable restrictions, once imposed, also continue to apply to the proceeds from the sale or lease of any charitable assets.13

- A nonprofit corporation is free to change its charitable purpose by amending its Articles of Incorporation, but such a change applies only to later-acquired funds, not to existing assets.14

The charitable use of existing assets can be changed only where there is a general charitable purpose and the specific charitable use has become illegal, impossible, or impracticable. In that case, the doctrine of cy pres requires the assets to be used for a charitable purpose that is as near as possible to the original charitable purpose.15 In certain circumstances, the donor may include in the initial gift a variance power, empowering the donee charity to alter the specific purposes of the gift if the governing body of the charity determines that such later alteration is warranted by changed circumstances.

III. Section 501(c)(3) – A Primer

This section of the outline first describes some of the basic rules that affect all Section 501(c)(3) organizations. It then discusses three special issues: unrelated business taxable income, excess benefits transactions, and public charity status.

A. Rules Applicable to All 501(c)(3) Organizations

IRC Section 501(c)(3) defines tax-exempt organizations as follows:

Corporations, and any community chest, fund, or foundation, organized and operated exclusively for religious, charitable, scientific, testing for public safety, literary, or educational purposes, or to foster national or international amateur sports competition (but only if no part of its activities involve the provision of athletic facilities or equipment), or for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals, no part of the net earnings of which inure to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual, no substantial part of the activities of which is carrying on propaganda, or otherwise attempting, to influence legislation (except as otherwise provided in subsection (h)), and which does not participate in, or intervene in (including the publishing or distribution of statements), any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.

Put more simply, in order to qualify as a tax-exempt charitable organization, an entity must be organized and operated for one or more of the exempt purposes listed above, and it must refrain from inurement, electioneering, and substantial lobbying.

1. Organizational Test

The organization’s governing document – whether articles of incorporation, articles of association, or a trust agreement – must meet certain requirements in order to satisfy the organizational test. The document must limit the charity’s purposes to one or more of the purposes listed in IRC Section 501(c)(3). Moreover, it must not “expressly empower the or-ganization to engage, otherwise than as an insubstantial part of its activities, in activities which in themselves are not in furtherance of one or more exempt purposes.”(Reg. Sec. 1.501(c)(3)-1(b)(1)(i)(b).) In practice, the charity must also include an affirmation that it will not engage in prohibited political activities. Finally, it must make clear that its assets are irrevocably dedicated to one or more exempt purposes. For a recent discussion of the parameters of this test, see the IRS website (www.IRS.gov/charities), article titled “Organizational Test – IRC 501(c)(3)” by Elizabeth Ardoin.

2. Operational Test

The operational test forms the heart of the discussion in this paper. IRC Section 501(c)(3), taken literally, requires an organization to be operated exclusively for exempt purposes. The Regulations, however, add some flexibility to what is known as the operational test. They make clear that a charity may qualify as such if it is operated primarily for exempt purposes. An “insubstantial part” of the charity’s activities may be devoted to non-exempt purposes. (Reg. Sec. 1.501.(c)(3)-1(c)(1).) Thus, a charity may operate a trade or business whose conduct is not related to the achievement of its exempt purposes without losing its charitable status under the tax law. (IRC Sections 511-515, generally; Reg. Sec. 1.501(c)(3)-1(e)(2).) And private interests may benefit from the charity’s activities if that benefit is an unavoidable incident of the charity’s otherwise proper activities. However, the operational test requires a charity to “establish that it is not organized or operated for the benefit of private interests such as designated individuals, the creator or his family, shareholders of the organization, or persons controlled, directly or indirectly, by such private interests.”(Reg. Sec. 1.501(c)(3)-1(d)(1)(ii).)

3. Prohibition of Inurement

IRC Section 501(c)(3) specifically requires that “no part of the net earnings of [the organization] inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual . . . .”The IRS Chief Counsel’s office has written that “[i]nurement is likely to arise where the financial benefit represents a transfer of the organization’s financial resources to an individual solely by virtue of the individual’s relationship with the organization, and without regard to accomplishing exempt purposes.”(Gen. Couns. Mem. 38,459 (July 31, 1980).)

The IRS takes the position that “all persons performing services for an organization have a personal and private interest [in that organization] and therefore possess the requisite relationship necessary to find private benefit or inurement.” (Gen. Couns. Mem. 39,670 (June 17, 1987).) The Tax Court, however, does not cast its net quite this broadly. Rather than assume that all employees are insiders when testing for inurement, the Tax Court has stated that an insider is one who has a unique relationship with the organization by which the insider, by virtue of his or her control or influence over the organization, can cause its funds or property to be applied for the insider’s private purposes. (American Campaign Academy v.U.S., 92 T.C. 1053 (1989).)

IRC Section 4958 provides the IRS with the ability to impose intermediate sanctions, short of revocation of exempt status, on insiders who engage in excess benefit transactions. As the law under Section 4958 evolves, it is likely that the definition of insiders or “disqualified persons” under Section 4958 will also be used to define insiders for purposes of the inurement prohibition. It is also likely that given the right to impose intermediate sanctions on insiders who profit from a charity improperly, the IRS is less likely to pursue revocations on grounds of inurement.

4. Prohibition of Electioneering

A charity may not support or oppose candidates for public office. The IRS considers this prohibition to be absolute. The Chief Counsel’s office has stated that “an organization described in IRC Section 501(c)(3) is precluded from engaging in any political campaign activities.”(Gen. Couns. Mem. 39,694 (Jan. 22, 1988).) Some activities that initially appear overtly political may not, however, constitute prohibited electioneering. Where students in a political science course were required to participate in political campaigns of their choosing as part of their course work, or where the college provided facilities and faculty advisors for a student newspaper that published student-written editorials on political matters, the IRS has ruled that the college was not itself breaking the rules against supporting or opposing candidates. (Rev. Rul. 72-512, 1972-2 C.B. 246; Rev. Rul. 72-513, 1972-2 C.B. 246.) A charity is also allowed to register voters, to urge registered voters to vote, and to educate voters, so long as its activities are nonpartisan. (IRC Section 4945(f); Reg. Sec. 53.4945-3(b); Rev. Rul. 78-248, 1978-1 C.B. 154.)

5. Prohibition of Substantial Lobbying

A charity may not devote a substantial part of its activities to attempting to influence legislation. However, charities that are neither churches nor private foundations may quite properly engage in legislative lobbying without risking their tax-exempt status, so long as lobbying remains an insubstantial part of their overall activities, by taking advantage of the provisions of IRC Sections 501(h) and 4911. The former defines substantiality with reference to a charity’s expenditures on lobbying, and the latter defines precisely what is and is not lobbying.

Even under the “insubstantiality” test, much advocacy commonly conducted by charities does not rise to the level of lobbying. A charity can attempt to influence the actions of government officials aside from legislative decisions, advocate its views through public interest litigation, convene conferences on public policy issues even if those issues are controversial, and express its views on those issues through advertisements, all without engaging in lobbying as the IRS understands the term.

B.Unrelated Business Taxable Income

Organizations that are tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code generally do not pay taxes on the income that they generate. There are two significant exceptions: private foundations pay a 2%, or sometimes 1%, tax on their investment income,16 and any Section 501(c) organization with UBTI pays UBIT on that income at the regular corporate tax rates.17

A Section 501(c) organization generates UBIT when it recognizes net income from:

- A trade or business, which is

- Regularly carried on, and which is

- Not substantially related to the organization’s exempt purpose.

If any one of these elements is absent, we need look no further – there is no UBIT.18

1. Trade or Business. A trade or business includes “any activity carried on for the production of income from the sale of goods or the performance of services.”19 The Regulations suggest that the term “trade or business” has the same meaning as it has under Section 162 in connection with analyzing the deductibility of business expenses.20 Although there have been cases that analyze the “trade or business” element of the test, and although it is possible to have an income-generating activity that is not a “trade or business,” as a practical matter, most potential UBIT matters that come to the attention of a practitioner are going to satisfy the “trade or business” element of the test.

2. Regularly Carried On. The Regulations provide that whether or not a trade or business is regularly carried on is determined by examining the “frequency and continuity with which the activities productive of the income are conducted and the manner in which they are pursued.” The stated purpose in the Regulations is “to place exempt organization business activities upon the same tax basis as the nonexempt business endeavors with which they compete.”21

The analysis of whether a particular activity is regularly carried on depends, of course, on all of the facts and circumstances, but the following guidelines can be drawn from the cases, rulings, and regulations, although the rulings and cases are by no means always consistent.

- It is important to compare the frequency and continuity of the activity with comparable activities being carried on by commercial entities. (Reg. 1.513-1(c)(1).) For example, if an activity is inherently seasonal, such as horseracing, then the regularity must be determined by examining the normal time span of comparable commercial activity. (Reg. 1.513-1(c)(2)(i).)

- An activity carried on one or two weeks a year is not likely to be regularly carried on, especially if other taxable entities engage in the same activity on a more regular basis. (Reg. 1.513-(c)(2)(i).)

- An activity carried on once a week, such as the operation of a commercial parking lot, each week of the year, is regularly carried on. (Reg. 1.513-1(c)(2)(i).)

- Annual or semi-annual fundraisers are typically not regularly carried on, even though they occur every year.

- In NCAA v. Commissioner, 914 F.2d 1417 (10th Cir. 1990), the Court held that advertising in the NCAA program was not a regular activity, because the tournament had a very limited two- to three-week duration, even though the NCAA spent much of the year selling the advertising space. The IRS does not follow this case, and it is probably not prudent to rely on this case, especially outside of the 10th Circuit.

- In Suffolk County Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, 77 T.C. 1314 (1981), the Court found that the production of an annual vaudeville show conducted over eight to sixteen weeks, including a printed program for the show that accepted advertisements, was not regularly carried on, even though the activities were conducted by professional fundraisers over a six-month period. The IRS acquiesced in this decision (AOD 1249, March 22, 1984), but it is not clear that the IRS would reach a similar conclusion today.

3. Substantially Related. Finally, if an exempt activity is substantially related to the organization’s exempt purpose, it does not generate UBIT. The Regulations indicate that an activity is related to exempt purposes “only where the conduct of the business activity has a causal relationship to the achievement of exempt purposes,” and the causal relationship must be substantial. (Reg. 1.513-1(d)(2).)

In analyzing whether a particular activity is substantially related to an organization’s exempt purpose, the organization must first examine the exempt purpose set forth in its own organizing documents and its own charitable purpose. An activity that may be related to Organization X’s exempt purpose may not be related to Organization Y’s. With careful planning, however, it may be possible for Organization Y to engage in this activity by amending its Articles of Incorporation to expand its purposes and by providing proper notice to the IRS of the amendment.

There are far too many cases and rulings addressing the “substantially related” test to summarize in this short outline, but some interesting ones include:

- In United States vs. American College of Physicians, 475 U.S. 834 (1986), the Supreme Court examined the sale of advertisements in a medical journal. The Court held that the manner of selection and presentation of the ads was not substantially related to the organization’s exempt purpose. The organization had argued that the purpose of the ads was to educate the readers, for example, about the products of pharmaceutical companies.

- The examples set forth in the regulations on travel tours provide insight into when the IRS considers travel tours to be substantially related to an organization’s exempt purpose.

- The museum gift shop rulings go to the heart of the substantially related test. They also illustrate the “fragmentation rule”; namely, that the IRS can look at a series of items sold in a gift shop (for example) and determine that some items, such as posters or cards depicting paintings, are substantially related and do not generate UBIT while other items, such as souvenirs of the city in which the museum is located, are not substantially related and do generate UBIT.22

- In PLR 200021056, the Service ruled that the operation of a gift shop and tea room by an organization established to aid deserving women to earn their own living through their handiwork was not substantially related to the particular organization’s exempt purpose.

- In PLR 200032050, the Service considered a question which exempt organizations pose from time to time: Can an organization rent real estate (debt financed) to other nonprofit organizations without being subject to UBIT? The ruling indicates that one must examine whether the rental arrangement and the activities of the lessee further the exempt purpose of the organization. An organization whose mission is economic development – to improve the quality of life of individuals and families in the inner city – can rent to organizations such as childcare providers and social service agencies that help it carry out those purposes. The logic of the ruling also suggests, however, that if this organization were to rent to a qualified (c)(3) organization whose mission was, for example, preserving the environment or religious study, the rental arrangement would not be substantially related.23

There are, of course, many other rulings and cases in this area. Some areas, such as the relatedness of associate member dues or insurance programs provided to members, have led to the development of significant bodies of law, while many issues that arise are supported by minimal precedential guidance.

C. Excess Benefits – Section 4958

Federal tax law addresses conflicts of interest in Section 4958 of the Internal Revenue Code, which prohibits excess benefit transactions between insiders in a charity (such as its directors, officers, and key employees) and the charity.

1. Excess Benefit Transactions. Excess benefit transactions are transactions in which an excessive economic benefit is provided by a public charity to a disqualified person. A benefit is excessive if the value of the benefit exceeds the value of what the charity received from the disqualified person. Typically, excess benefit transactions involve compensation of insiders, but they can also involve the sale or other transfer of a charity’s property, and they can involve the use by a disqualified person of a charity’s property, including intellectual property.

2. Disqualified Persons. Disqualified persons are persons who are, or in the previous five years have been, in a position to exercise substantial influence over the charity’s affairs. The following persons are deemed to have substantial influence: each member of the Board of Directors; the president, chief executive officer, chief operating officer, treasurer, and chief financial officer; such persons’ spouses, ancestors, children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, brothers, and sisters; the spouses of the children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, brothers, and sisters; and any entity in which such persons hold more than 35% of the control. For a corporation, this means more than 35% of the voting power, for a partnership it means more than 35% of the profit interest, and for a trust it means more than 35% of the beneficial interest. In addition, the Board may determine that other persons exercise substantial influence over the charity’s activities based on facts and circumstances. Such persons could include the founder of the charity, a substantial contributor to the charity, a person with managerial authority over the charity, or a person with control over a significant portion of the charity’s budget.

3. Establishing the Presumption of Reasonableness. Normally, when a charity engages in a transaction with a disqualified person (such as a major donor or a Board member), the charity must be prepared to demonstrate that it has taken appropriate steps to ensure that it is not providing an excess benefit to the insider.

Regulations to Section 4958 (the “Regulations”) describe the steps an organization may take to create a presumption that no excess benefit transaction occurs and to shift the burden of proof onto the IRS. Under Section 53.4958-6 of the Regulations, payments under a compensation arrangement will be presumed to be reasonable, and a transfer of property or services between a charity and a disqualified person is presumed to be at fair market value, if the following conditions are satisfied:

- The compensation arrangement or terms of transfer are approved in advance by the charity’s governing body, or by a committee of the governing body composed entirely of individuals who do not have a conflict of interest with respect to the arrangement or transaction; and

- The governing body or committee obtained and relied upon appropriate data as to comparability before making its decision; and

- The governing body or committee adequately documented the basis for its decision concurrently with making that decision.

In order to ensure that the Board of Directors is not inappropriately influenced by a director with a conflict of interest, the Regulations provide that a director with a conflict of interest can meet with other members of the Board only to answer questions. The director should otherwise recuse him- or herself from the meeting and should not be present during debate and voting on the transaction in question.

The Regulations provide some examples, but not an exhaustive list, of the type of data that is considered appropriate when considering comparability. In the case of compensation, relevant information includes compensation levels paid by similarly situated organizations for functionally comparable positions; the availability of similar services in the geographic area; independent compensation surveys compiled by independent firms; and actual written offers from similar institutions competing for the services of the disqualified person. In the case of property, the Regulations provide that relevant information includes, but is not limited to, current independent appraisals of the value of all property to be transferred, and offers received as part of an open and competitive bidding process. Treas. Reg. Section 53.4958-6(c)(2).

For the decision to be documented adequately, the written records of the governing body or committee must note (1) the terms of the transaction that was approved and the date it was approved; (2) the members of the Board or committee who were present during the debate on the transaction or arrangement that was approved and those who voted on it; (3) the comparability data obtained and relied upon by the Board or committee and how the data was obtained; and (4) the actions taken in order to appropriately exclude directors with a conflict of interest while the transaction was considered. The records must be prepared by the later of the next meeting of the Board or committee or 60 days after the final action regarding the transaction was taken, and must be approved within a reasonable time after that.

4. Penalty taxes. Section 4958 creates a two-tier excise tax structure on excess benefit transactions. The initial tax is 25% of the excess benefit resulting from each excess benefit transaction. The 25% tax is payable by the disqualified person. If the 25% tax is {00160421.DOC; 4}21 imposed on an excess benefit transaction and the disqualified person does not correct the excess benefit within a certain amount of time, a second-tier tax of 200% of the excess benefit is imposed on the disqualified person. For example, if a Section 501(c)(3) organization was found to have paid $150,000 to a disqualified person in a transaction for which $100,000 was fair market value, the disqualified person would have to pay a tax of 25% of $50,000, or $12,500, to the IRS. In addition, the disqualified person would have to return the excess benefit of $50,000 to the organization, or be subject to the added 200% penalty tax (of $100,000).

Finally, a 10% tax is imposed on the Board of an organization if the Board knowingly and willingly participated in the excess benefit transaction, up to a total of $10,000 for each excess benefit transaction. The Board will not be considered to have knowingly participated if (1) after making full disclosure of the facts to an appropriate professional, the Board relies on the professional’s reasoned written opinion regarding the elements of the transaction within the professional’s expertise, or (2) the Board relies on the fact that the requirements for the rebuttable presumption of reasonableness have been satisfied. Treas. Reg. Section 53.4958-1(d)(4)(iii) and (iv).

D. Public Charities and Private Foundations

Tax-exempt status under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code permits a charitable organization to pay no tax on any operating surplus it may have at the end of a year, and it permits donors to claim a charitable deduction for their contributions.

There is a further division in the world of Section 501(c)(3) organizations, classifying them into private foundations and public charities. A special regulatory scheme applies to private foundations in addition to the basic rules governing all charities. The private foundation laws impose a 2% tax on investment income, limit self-dealing and business holdings, require annual distributions, prohibit lobbying entirely, and restrict the organization’s operations in other ways. Also, large donors to a private foundation have a lower ceiling on the amount of deductible gifts they can claim each year. In most circumstances, public charity status is preferable to private foundation status.

A Section 501(c)(3) organization can avoid private foundation status, and thus be classified as a public charity, in any of three ways: (1) by being a certain kind of institution, such as a church, school, or hospital; (2) by meeting one of two mathematical public support tests; or (3) by qualifying as a supporting organization to another public charity. In this memo, we discuss the two mathematical public support tests.

1. The Public/Governmental Support Test of Sections 170(b)(1)(A)(vi) and 509(a)(1)

This public support test was designed for charities which derive a significant proportion of their revenues from donations from the public, including foundation grants, and 22 from governmental grants. The test has two variations. If an organization can satisfy either of the two variations of this support test, it will qualify as a public charity under Sections 170 (b)(1)(A)(vi) and 509(a)(1).

The first variation is known as the one-third test. A charity can satisfy this test if public support is one-third or more of the total support figure. Nothing more is needed if this mathematical fraction is attained.

The second variation, known as the 10% facts and circumstances test, has two requirements. First, the charity’s public support must be at least 10% of its total support. Second, the charity must demonstrate, with reference to facts and circumstances specified by the IRS, that it is operated more like a public charity than like a private foundation.

In order to determine which test applies to your organization, you must begin with the mathematical public support computation.

The first step in that computation is to determine two figures: total support and public support.24 These figures are, respectively, the denominator and the numerator of the public support fraction. They are computed with reference to the charity’s revenues over a specific measuring period, which is usually four years in length; in the case of newly formed organizations, the measuring period is five years.25 In both instances, however, the figures are based on the revenues for the entire period. It is not a year-by-year calculation.

a. Total Support (Support Base, Denominator). To determine the charity’s support base, which is the denominator of the fraction, we add the following revenue items for the measuring period:

- Gifts, grants,26 contributions, and membership fees received.

- Gross investment income (e.g., interest, dividends, rents, royalties, but not gains from sale of capital assets).

- Taxable income from unrelated business activities,27 less the amount of any tax imposed on such income.

- Benefits from tax revenues received by the charity, and any services or facilities furnished by the government to the charity without charge, other than those generally provided to the public without charge.

- All other revenues, except for:

– Gains from the sale of capital assets.

– Gross receipts from admissions, merchandise sold or services per-formed, furnishing of facilities, or other business activities related to the charity’s exempt purposes.

– Unusual grants, as defined by the IRS.

b. Public Support (Numerator). The numerator of the fraction consists of that portion of total support which falls within the following defined classes of revenue:

- Government grants (not fee-for-service contracts) are included in full.

- Gifts, grants, contributions, and membership fees from other public charities qualified under Section 170(b)(1)(A)(vi) are included in full.

- Gifts, grants, contributions, and membership fees from all other sources are counted in full, so long as the amount from each source does not exceed 2% of total support – that is, 2% of the denominator.

- Larger gifts, grants, contributions, and membership fees may be counted up to 2% of the total support figure, but no more. Any amounts above that figure are not counted as public support. Note: When applying the 2% limit, amounts from certain related family members, and from businesses and their major owners, are combined and treated as coming from one source.

- Benefits from tax revenues received by the charity, and any services or facilities furnished by the government to the charity without charge, other than those generally provided to the public without charge, are counted in full.

c. The One-Third Test. If the public support figure is one-third or more of the total support figure, when the two are combined in a fraction, the organization will qualify automatically as a public charity.

d. The 10% Facts and Circumstances Test. If the public support fraction is less than one-third but more than one-tenth, the organization turns to the alternate public support test for donor-supported charities. The organization must provide evidence to the IRS that it meets the following two requirements:

(A) Attraction of Public Support. The organization must be so organized and operated as to attract new and additional public or governmental support on a continuous basis. This can be done in one or both of two ways:

(1) By maintaining a continuous and bona fide program for solicitation of funds from the general public, community, or membership group involved.

(2) By carrying on activities designed to attract support from governmental units or other public charities.

The IRS considers whether the scope of fundraising is reasonable in light of the organization’s charitable activities, and recognizes that fundraising may be limited to those persons most likely to provide seed money in its early years.

(B) Multi-Factor Analysis. The organization must show that it is in the nature of a publicly supported organization, taking into account five factors. It is not generally required that all five factors be satisfied. The factors relevant to each case and the weight accorded to any one of them may differ, depending upon the nature and purpose of the organization and the length of time it has been in existence. The factors are:

(1) Percentage of financial support.This provides that the higher the percentage of public support above 10%, the lesser will be the burden of satisfying the other factors. If the percentage is low due to sizable investment income on an endowment, the IRS will consider whether the endowment came from public or government sources, or from a limited group of donors.

(2) Sources of support.This factor focuses on whether the public support comes from government or a “representative number of persons,”rather than receiving almost all of its support from members of a single family. Consideration is given to the type and age of the organization, and to whether it appeals to a limited constituency geographically or otherwise.

(3) Representative governing body.This factor looks at whether the organization’s governing body represents the broad interests of the public, or the personal or private interests of a limited number of donors. Boards meeting this factor include those comprised of:

(a) Public officials acting in their official capacities.

(b) Persons having special knowledge or expertise in the particular field or discipline in which the organization is operating.

(c) Community leaders, such as elected or appointed officials, clergymen, educators, civic leaders, or other such persons representing a broad cross-section of community views and interests.

(d) For membership organizations, individuals elected by a broadly based membership.

(4) Availability of public facilities or services; public participation in programs or policies.This factor considers evidence that the organization:

(a) Provides facilities or services directly for the benefit of the general public on a continuing basis; e.g., museum, orchestra, nursing home.

(b) Publishes scholarly studies that are widely used by colleges, universities, or members of the public.

(c) Conducts programs participated in or sponsored by people having special knowledge or expertise, public officials, or civic or community leaders.

(d) Maintains a definitive community program, such as slum clearance or employment development.

(e) Receives significant funds from government or a public charity to which it is contractually accountable.

(5) Additional factors for membership organizations.These are:

(a) Whether dues-paying members are solicited from a substantial number of persons in a community, area, profession, or field of special interest.

(b) Whether dues for individual members are designed to make membership available to a broad cross-section of the interested public.

(c) Whether the activities of the organization would appeal to persons having a broad common interest or purpose; e.g.,alumni associations, musical societies, PTA’s.

2. The Exempt Function Income Test of Section 509(a)(2)

The mathematical public support test described in Section 509(a)(2) was designed for charities which sell services or materials to the public. Most of their income comes from these activities, rather than from donations or investment income.

To qualify a public charity under Section 509(a)(2), a charity must first compute its total support during the measurement period. It must then compute two fractions: its percentage of investment income, which may not exceed 331/3% of the total, and its percentage of public support, which must exceed 331/3% of the total. Each of these computations must be determined on the cash method, rather than the accrual method, of accounting.

a. Total Support. The charity first determines its total revenues during the period in question. As you will see from the charts on pages 28-29, in order to compute the charity’s public support level, this figure must be computed both annually and in the aggregate, for the entire applicable period. The figure is the sum of the support received by the charity in the form of:

- Gifts, grants,28 contributions, and membership fees received.

- Gross receipts from admissions, merchandise sold or services performed, furnishing of facilities, or other business activities related to the charity’s exempt purposes.

- Gross investment income (e.g., interest, dividends, rents, royalties, but not gains from sale of capital assets).

- Taxable income from unrelated business activities,29 less the amount of any tax imposed on such income.

- Benefits from tax revenues received by the charity, and any services or facilities furnished by the government to the charity without charge, other than those generally provided to the public without charge.

The sum of all of these items, for the period in question, is the denominator of the fraction for each of the two Section 509(a)(2) tests.

b. The Investment Income Limitation. In order to satisfy the Section 509(a)(2) investment income test, a charity must normally30 receive not more than one-third of its total support, as defined above, from the third and fourth sources listed above – that is, from gross investment income31 (other than capital gains) and unrelated business taxable income (less tax on that income). In other words, at the end of each measuring period, the charity must compute a fraction whose denominator is total support, and whose numerator consists of non-capital-gain gross investment income and unrelated business taxable income net of tax. If this fraction is more than one-third, the charity cannot qualify under Section 509(a)(2), even if it satisfies the public support requirements to which we now turn.

c. The Public Support Threshold. The second of the two Section 509(a)(2) support tests requires the charity to derive at least one-third of its total support from donations, membership fees, and exempt function gross receipts. This fraction should be computed each year for a four-year period consisting of the prior year and the three immediately preceding years. As noted above, the entire amount of donations, membership fees, and exempt function gross receipts for the period in question must be included in the denominator of the fraction. Depending on the source and amount of the funds, however, the amount that may be included in the numerator of the fraction may vary from 0 to 100%. Tables I and II set forth what portions of these income categories may be allocated to the numerator of the fraction.

Table I

Gifts, Grants, Bequests, Memberships, and Government Support:

How Much Is Included in the Numerator of

the Public Support Fraction?

| SOURCE | INCLUDIBLE AMOUNT |

| A governmental bureau or unit | 100.00% |

| A Section 509(a)(1) public charity | 100.00% |

| A disqualified person | None |

| Individuals and entities that have not become disqualified persons by the end of the measuring period | 100.00% |

| Benefits from tax revenues, and government services or facilities furnished at no charge | 100.00% |

Table II

Gross Receipts from the Performance of Exempt Functions:

How Much Is Included in the Numerator of

the Public Support Fraction?

| SOURCE | INCLUDIBLE AMOUNT |

| A governmental bureau or unit | Amounts received in a taxable year up to the greater of $5,000 or 1% of the total support received by the charity in that taxable year |

| A Section 509(a)(1) public charity | Amounts received in a taxable year up to the greater of $5,000 or 1% of the total support received by the charity in that taxable year |

| A disqualified person | None |

| Individuals and entities that have not become disqualified persons as of the end of the taxable year | Amounts received in a taxable year up to the greater of $5,000 or 1% of the total support received by the charity in that taxable year in that taxable year |

The tables contain several technical terms whose meaning is important to understand: governmental bureau or unit, Section 509(a)(1) public charity, and disqualified person.

(1) A government bureau or unit includes any agency or department of the federal government or any state or local government. For purposes of the 1% or $5,000 limitation, each government bureau or unit is treated as a separate payor.

(2) In order to qualify for public charity status under Section 509(a)(1), a charity must either perform what Congress considers to be an inherently public function – schools, churches, hospitals, and other functions described in Section 170(b)(1)(A)(i)(v) – or derive its support from a sufficiently diverse donor pool to satisfy the mathematical support test described in Section 170(b)(1)(A)(vi).

(3) A disqualified person32 may be an individual or a legal entity, such as a corporation or trust, which is described in any of the following categories, and which is neither a governmental bureau or unit nor a public charity described in Section 509(a)(1):

- Substantial contributor: one whose gifts or bequests to the charity exceed the greater of $5,000 or 2% of the total amount of donations and bequests received by the charity from its formation through the end of the taxable year in which the gift is made.

- Owner of a substantial contributor: any person who owns more than 20% of a corporation, partnership, or trust that is itself a substantial contributor.

- Foundation manager: an officer, director, trustee, or employee with equivalent responsibilities.

- Family member: Disqualified person status is attributed to ancestors and descendants of substantial contributors, foundation managers, and their spouses. Brothers and sisters of disqualified persons are not treated as disqualified persons by virtue of that relationship.

- Related legal entities:If any person or entity described above owns more than 35% of the total voting power of a corporation, more than 35% of the profits interest in a partnership, or more than 35% of the beneficial interest in a trust, the corporation, partnership, or trust is itself a disqualified person.

This regulatory framework has very practical consequences for organizations that seek to qualify as public charities under Section 509(a)(2). Chief among them is the need to establish tracking and monitoring systems so that the organization and its advisors can assess the organization’s compliance with the public charity tests.

Charities that receive grants from governmental agencies or from Section 509(a)(1) public charities, as well as fees for exempt-function services or products, should bear in mind that grants from such organizations are counted in full in the numerator of the public support fraction, while fees for services or products are subject to the $5,000 or 1% annual ceiling. The line between grants and gross receipts is not always clear, especially where the charity is producing a service or product at the request of the payor. The fundamental question is what the charity is providing in return for the payment, and who is receiving the product. Where the charity provides the payor organization with a service or work product that primarily benefits the public, rather than primarily benefiting the payor, the IRS will treat the payment as a grant. If there is any question how a payment should be classified, a charity should consult its legal counsel or its accountant.

IV. The Nonprofit Integrity Act (“NIA”)

SB 1262, the Nonprofit Integrity Act of 2004, became effective on January 1, 2005. SB 1262, as it finally emerged after extensive amendments, addresses two broad areas of nonprofit activity: governance of charitable organizations and fundraising by or on behalf of charitable organizations.

This section of the outline explains the governance provisions of the Act: the requirements for financial audits, for audit committees, for public disclosure of audited statements, and for review and approval by the board of directors of the compensation paid to the chief executive officer and the chief financial officer of the charitable organization. It also discusses some of the Act’s extensive charitable fundraising provisions.

A. Governance

1. Financial Audits

SB 1262 was passed in the wake of corporate scandals, such as Enron and WorldCom, that revealed to the nation the questionable financial practices of some of the nation’s largest corporations. It was intended in part to be an analog to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which addresses the financial accountability of for-profit corporations. As such, SB 1262 focuses on the financial practices of nonprofit organizations in an effort to ensure that adequate accountability exists.

SB 1262 attempts to institute independent oversight of the financial practices of charities. Specifically, it requires certain charities to prepare annual financial statements audited by independent certified public accountants. The charities subject to this new requirement are those charitable corporations, unincorporated associations, and charitable trusts required to file reports with the Attorney General. This includes foreign corporations doing business or holding property in California for charitable purposes.33 On the other hand, educational institutions, hospitals, cemeteries, and religious organizations are exempt from the obligation to file reports with the Attorney General and, therefore, are not subject to either this mandatory audit requirement, or to the requirements for audit committees and for public disclosure of audited statements discussed later below.34

The mandatory audit requirement applies to some but not all charitable organizations subject to the Act. Only a charitable organization that receives or accrues in any fiscal year gross revenues of $2 million or more must meet the audit requirement. Grant or contract income from the government is not included in the charitable organization’s gross revenue aslong as the governmental entity requires an accounting of those funds.

The financial audit must be performed by an independent certified public accountant in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). If the audit firm also performs non-audit functions for the charity, the firm and its auditors must conform to the standards for auditor independence set forth in the Government Auditing Standards issued by the Comptroller General of the United States (the Yellow Book, accessible online at http://www.gao.gov/govaud/ybk01.htm), but the Attorney General may prescribe standards for auditor independence different from those in the Yellow Book.35

2. Public Disclosure of Audited Statements

Audited statements (those required by the Act, as well as those prepared by charitable organizations required to file reports with the Attorney General, even if not required by the Act) must be made available for inspection by the Attorney General and the general public within nine months after the close of the fiscal year to which the statements relate. The Act adopts the same rules for public disclosure already applicable to IRS Form 990. Thus, audited statements must be made available to the public for a period of three years, both (1) at the charitable organization’s principal and any regional or district office during regular business hours, and (2) by mailing a copy to any person who so requests in person or in writing; or, alternatively, by posting the audited statements on the charitable organization’s website.36

3. Audit Committees

With regard to those charities required by the Act to prepare annual audited financial statements as described above, the Act also provides that charities in corporate form –including charitable corporations incorporated outside California but required to register with California’s Attorney General – must appoint an audit committee consisting of at least one member. The committee must be appointed by the board of directors.

The audit committee may include non-board members. While it may include members of the finance committee (if one exists), the chair of the audit committee may not be a member of the finance committee, and members of the finance committee must constitute less than half of the audit committee. The audit committee may also not include any member of the staff, including top management, or any person who has a material financial interest (to be determined based on the facts and circumstances of the specific case) in any entity doing business with the charitable organization. Officers who are not staff members may serve.

If audit committee members are paid, they may not receive compensation in excess of the amounts received, if any, by members of the board of directors for service on the board.

The audit committee serves subject to the supervision of the Board but is given five specific duties by the Act. Audit committees:

1. shall recommend to the board of directors the retention and termination of the independent auditor,

2. may negotiate the compensation of the auditor on behalf of the board,

3. shall confer with the auditor to satisfy the committee members that the financial affairs of the charitable organization are in order,

4. shall review and determine whether to accept the audit, and

5. shall approve performance of any non-audit services to be provided by the auditing firm.37

Essentially, the audit committee’s function is to ensure that extra care is taken with respect to the corporation’s finances.

4. Compensation Review

The Act provides that compensation, including benefits, of two officers (the chief executive officer and the chief financial officer) must be reviewed and approved by the board of directors or an authorized committee of a charitable corporation or unincorporated association, or by the trustee or trustees of a charitable trust. The approving body must determine that the compensation is just and reasonable.38 This requirement applies to all entities, not just those which meet the $2 million floor on gross revenues described above. The Act only requires review of the compensation of the chief executive officer and chief financial officer, even if other offices are more highly compensated..

Review and approval must occur when the officer is hired, when the term of employment of the officer is renewed or extended, and when the compensation package is modified, unless the modification applies to substantially all employees.

B. Fundraising

In addition to financial accountability, the Act also focuses on fundraising. It requires charitable organizations to enter into written contracts containing mandatory terms and conditions for every charitable fundraising event where a commercial fundraiser is used. It also requires charitable organizations to exercise control over fundraising activities conducted for them. A discussion of all of these provisions is beyond the scope of this outline, as many of the requirements fall upon the fundraisers themselves, rather than the charitable organization. Nevertheless, a basic understanding of these provisions is essential for all organizations that work with professional fundraisers.

1. Commercial Fundraiser and Fundraising Counsel: Definitions

The Act only applies to commercial fundraisers and fundraising counsel. For purposes of this outline, consider any professional fundraiser who receives a fee to fall under one of the relevant categories.39

2. Charitable Organizations: Control over Fundraising

The Act makes plain that charitable organizations must “establish and exercise control,” not only over their own fundraising activities, but over fundraising activities conducted by others for their benefit. That control must include approval of all written contracts, and the charitable organization must assure that fundraising activities are conducted without coercion of potential donors.40

A charitable organization may not contract with any commercial fundraiser unless that fundraiser has registered as required with the Attorney General’s Registry of Charitable Trusts (“Registry”),41 nor may charity A raise funds for charity B unless charity B is registered as required.42

3. Misrepresentations

Charitable organizations may not misrepresent the purpose of the charitable organization or the nature or purpose or beneficiary of a solicitation. Misrepresentation may be established by word, by conduct, or by failure to disclose a material fact.43 The Act sets forth twelve prohibited acts and practices in the planning, conduct, or execution of any charitable solicitation or sales promotion.44 The prohibitions apply to, according to the Act, “regardless of injury”.45

4. Contracts

The Act requires that a fundraiser and a charitable organization must enter into a written contract for each solicitation campaign, event, or service.46 The contract must be signed by an authorized contracting officer for the commercial fund-raiser and by an official authorized to sign by the charitable organization’s governing body. The mandatory provisions of the contract, which may be inspected by the Attorney General, include:

1. A statement of the charitable purpose of the fundraiser.

2. A statement of the “respective obligations” of the commercial fundraiser and the charitable organization.

3. If the fundraiser is to be paid a fixed fee, the contract must state the fee and provide a good faith estimate of what percentage the fee will be of total contributions, disclosing the assumptions on which the estimate is based, which must reflect all relevant facts known to the fundraiser.

4. If the fundraiser is to be paid a percentage fee, a statement of the percentage of total contributions that will be remitted to or retained by the charitable organization or, if the sale of goods is involved, the percentage of the sales price remitted to or retained by the charitable organization. In determining the percentage, the fundraiser’s fee, as well as any other amounts the charitable organization is required to pay as fundraising costs, must be subtracted from contributions and sales receipts received.

5. The starting and ending dates of the contract and the date solicitation activity will begin in California.

6. The contract must require the fundraiser to handle contributions in accordance with the Act’s requirements (discussed above) on the deposit or delivery of funds to the charity.

7. A statement that the charitable organization shall exercise control and approval over the content and frequency of any solicitation.

8. If the fundraiser proposes to pay any person or legal entity, in cash or in kind, to attend, sponsor, approve, or endorse a charity event, the maximum dollar amount of those payments must be stated.

The contract must also contain three distinct provisions relating to cancellation of the contract.

1.The contract must allow the charitable organization to cancel the contract without cost, penalty, or liability for a period of 10 days after signing, by giving written notice in a specified manner. Any funds collected by the fundraiser after notice of cancellation shall be held in trust for the benefit of the charitable organization without deduction for costs or expenses.

2.The contract must permit the charitable organization to terminate the contract on 30 days’ written notice to the fundraiser, effective five days after the notice is mailed. The charitable organization remains liable for the fundraiser’s services during the 30-day period.

3.The contract must provide that, after the initial 10-day cancellation period, the charitable organization may terminate the contract at any time by giving written notice, without payment of any kind to the fundraiser, if (1) the fundraiser makes material misrepresentations in solicitations or about the charitable organization, (2) the charitable organization learns that the fundraiser or its agents have been convicted of a crime punishable as a misdemeanor or felony, arising from charitable solicitation, or (3) the fundraiser otherwise conducts fundraising activities that cause or could cause “public disparagement of the charitable organization’s good name or good will.”47

Whenever a charitable organization cancels a contract, it must mail a duplicate copy of the notice of cancellation to the Registry.48 Contract cancellation rights are separate rights, entirely apart from the terms of any contract. Thus, even if contracts fail to spell out the required rights of cancellation, the Act provides that charitable organizations nevertheless have those rights by law.49 The Act also provides that charitable organizations may void contracts with commercial fundraisers or fundraising counsel if they are not properly registered.50

V. Director Liability and Protections

Individuals serve on nonprofit boards to provide a public service. They exercise their fiduciary duties as directors because they want to be good, effective directors and because they care about the organizations they serve, and not principally because they want to avoid being sued. Nonetheless, when lawyers talk about the duties and responsibilities of directors, we often think in terms of avoiding liability. In reality, the most effective way that a director can avoid liability is precisely to act diligently and with attention to the director’s fiduciary duties.

Consider some of the possible claimants who might file suit or assert a claim against a nonprofit director:

- Fellow officers or directors who believe that one or more of the directors acted without care or in bad faith (Law Section 5142, 5233);

- Members (if any) of the corporation for the same reasons (Law Section 5142, 5710);

- The California Attorney General (“AG”) if the AG believes a director (a) is responsible for causing the corporation to squander charitable assets or (b) has been involved in a self-dealing transaction (Law Section 5142, 5233, 5250);

- Employees who claim wrongful termination, harassment, or discrimination and who believe that the directors are responsible;